Fractured Communities

While Salt of the Earth faithfully depicts the violence and tension picketers faced, it’s important to recognize what transpired outside the narrative of the film as well as beyond the strike itself.

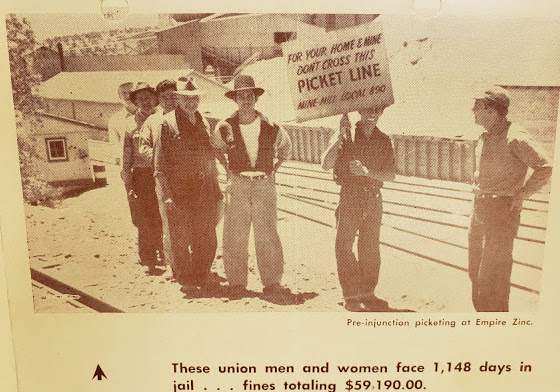

As Ellen Baker, author of On Strike and On Film, explains “failing to stop the women’s picket, the permanent injunction instead prompted a new round of…clashes” (128) both on and away from the picket-lines.

Tomas Carillo, a child from one of the strikers, was awakened one night by a man who opposed the strike. According to Carillo, “My bedroom was right there, and I saw a man, a silhouette, in the light of the moon. I knew if I moved the guy would think I was my dad and he’d shoot me” (Baker 129).

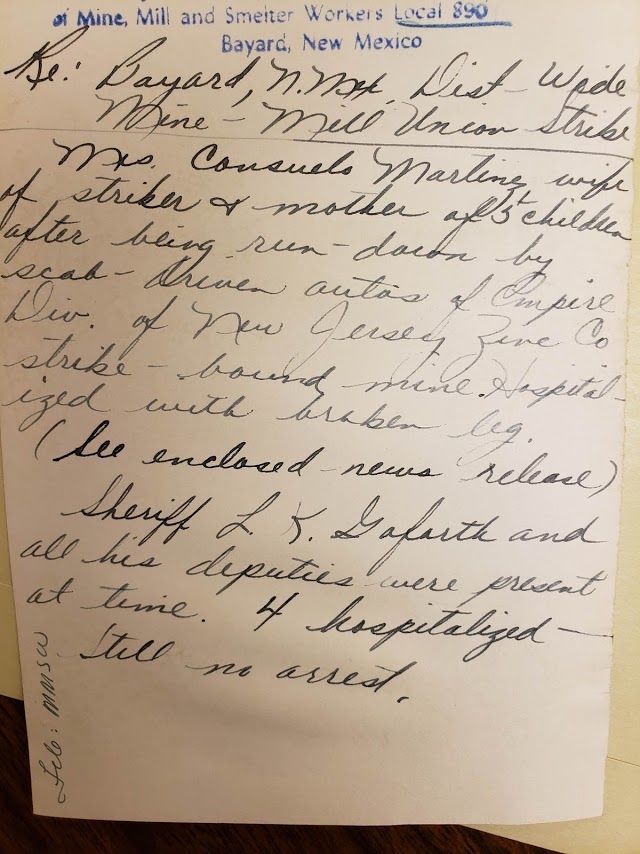

Another incident explains how Henry and Anselma Polanco were driving to Hanover for the strike when a man, Francisco Franco, overturned their vehicle. The Polancos were taken to the hospital and treated for bruising, cuts, and a broken ankle.

While violence against picketers was rampant, communities in Hanover and surrounding areas continued to splinter as the strike unfolded, and picketers ultimately retaliated against strikebreakers. Baker explains:

“Five men attacked Luis Hinojosa, a strikebreaker, and there is some question of whether they also attacked his pregnant wife when the couple was leaving the Empire Zinc area. Women threw red pepper on the strikebreakers and poked them with straight pins. Children threw rocks at strikebreakers, and they sabotaged strikebreakers’ cars by burying boards with nails in the dirt roads and by stuffing gas tanks with tailings from the mine” (130).

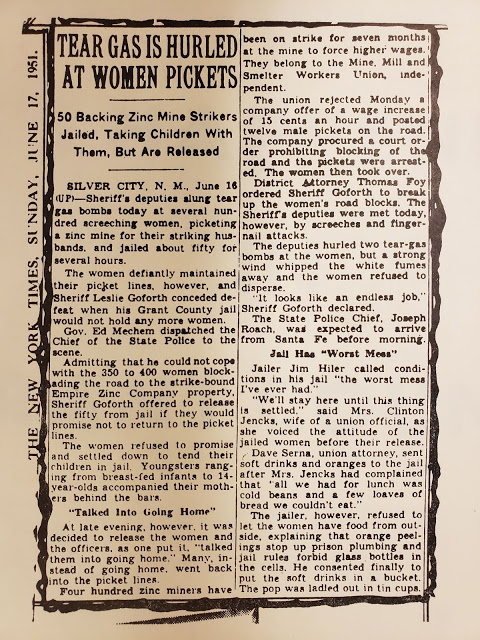

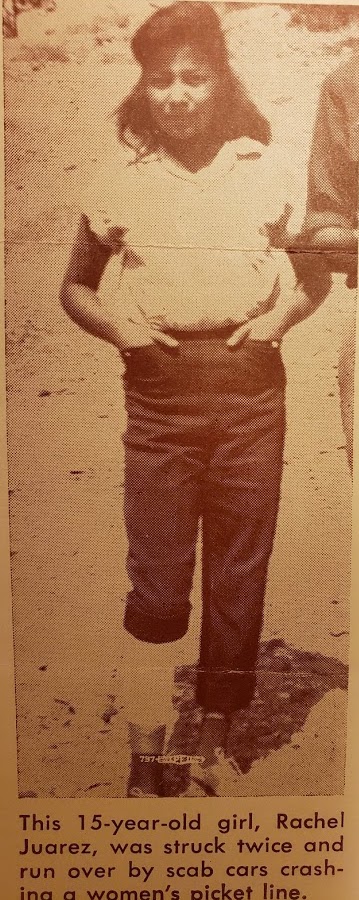

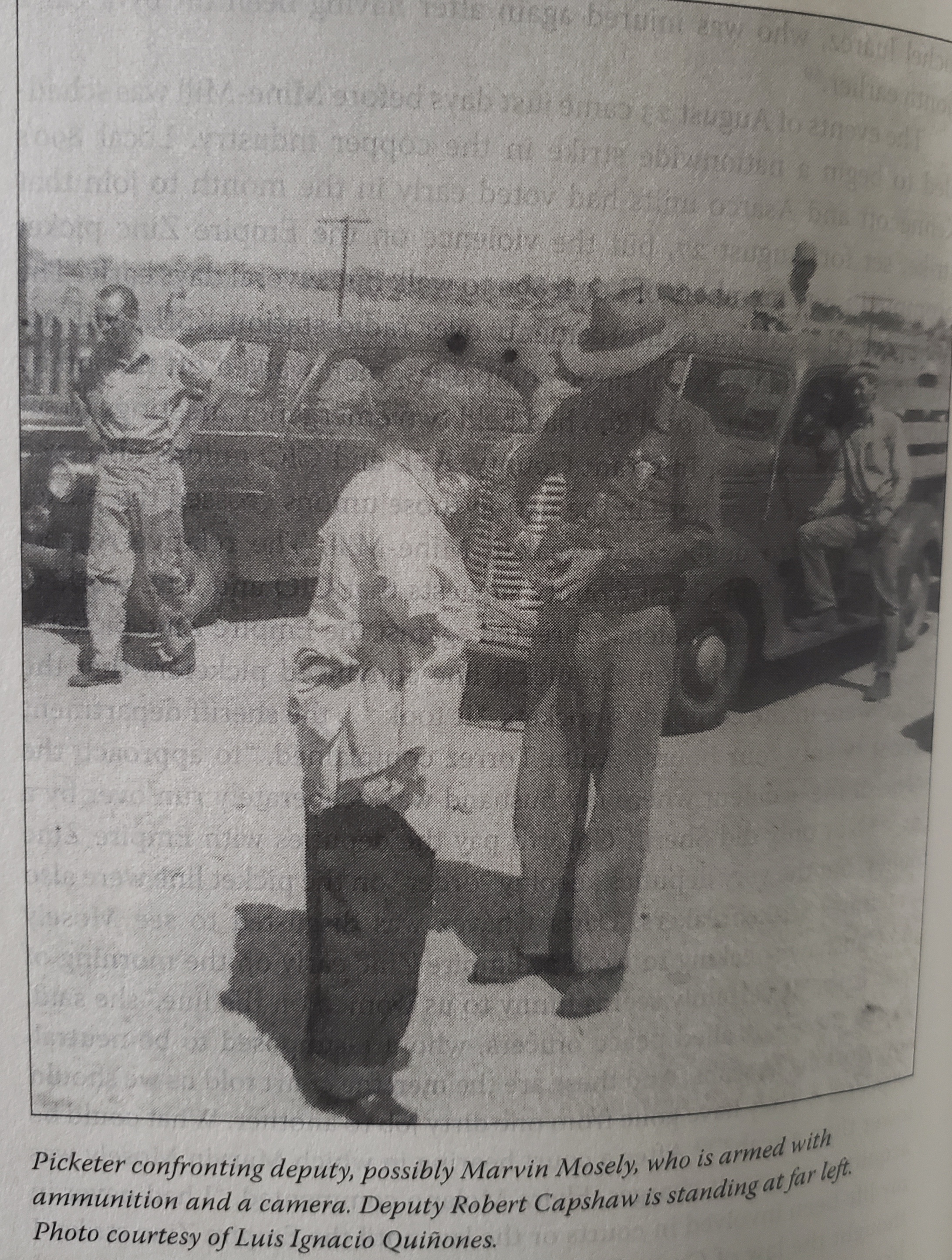

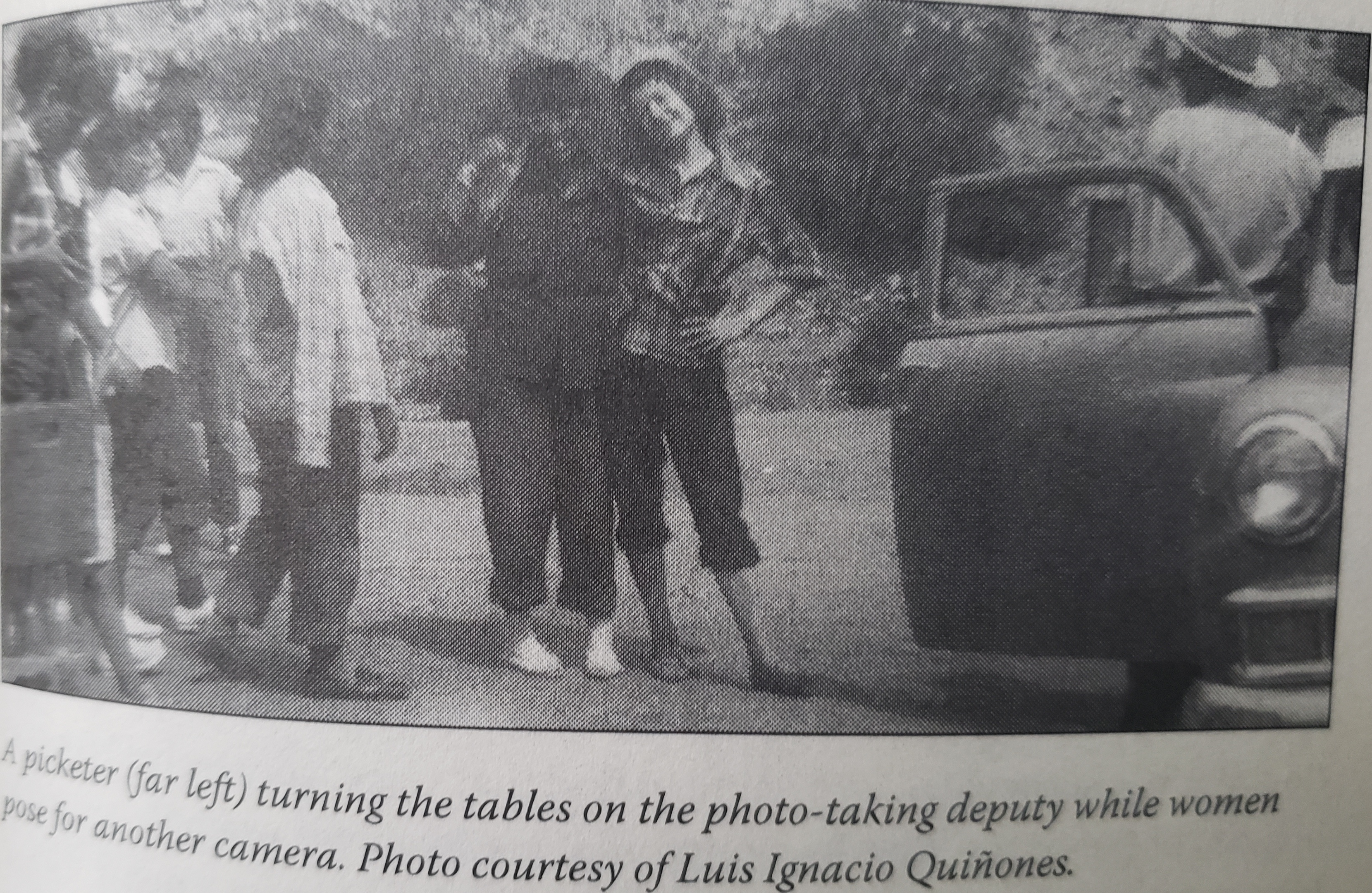

Tensions between strikers, strikebreakers, and authorities only intensified throughout the strike. On August 23rd, 1951, according to the Silver City Daily Press, five cars of strikebreakers approached the picket line which was blocking the road with forty or so women and children. The strikers struggled to hold the cars back, and when one car made its way through, four picketers were seriously injured. Another strikebreaker “‘jumped out of the car with a gun…and began shooting’ at the women. He wounded… Augustin Martinez, a war veteran who had been discharged from the army just nine days earlier” (Baker 130). Rachel Juarez Valencia, who was 14 at the time of the strike, describes her experience while picketing:

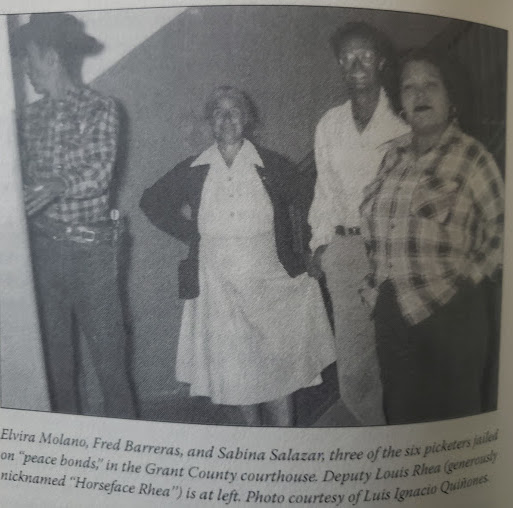

“My father who was a member [of the Local 890], came home and told me that I was going to be taking my sister’s place, because she was pregnant at the time and didn’t want her on the picket line. It was in the summer. I was out of school. Corina Rivera would pick me, Camerina Andazola and her two children up. Willie Andazola was one of the two children. Sometime during the summer, as the women were picketing, the district attorney Thomas Foy, gave the sheriff and some deputies permission to break the women’s picket line. We didn’t anticipate the violence that would come. As I was going around the circle, one of the cars that a deputy was driving caught me by surprise. As it was moving fast, the only thing I could do was hold on to the hood of the car the best way I could. I was able to hold on for approximately fifty feet. At that time, I knew I was either going to go under the car or I had to throw myself to the side of the road, which I did. As I lay on the ground, I could see some women coming to get me. I could see that a car had completely run over Mrs. Consuelo Martinez, an elderly lady of about seventy-five at the time. The women dragged me back to the side of the rode and the deputies started to arrest us. Some of the men who had been overseeing us, dragged Mrs. Martinez to the side of the rode so they wouldn’t run over her again. One of the men was shot on the leg because he was trying to help us. One of the deputies threw me in the back of his car and he took me to the Watts clinic in Silver City. I had a dislocated shoulder. They took care of it at the clinic and released me. The deputy drove me to the court house and into the jail. The jail cell where they put me was very overcrowded. The women moved the children and teenagers to the front of the cell, which had slats, so they could breathe better. A ninety-year-old lady named Bersabe Rosales was placed on a bed because she was ninety-years-old at the time and she was passing out. My dad heard about the violence in Hanover at his job at Kennecott in Santa Rita through the radio. He knew that I was supposed to be there and left his job to go to the court house to see what was going on. He did not know I was hurt and was hoping I was not jailed. They let us out after many complaints from the community who became outraged about having women and children in jail because we had already spent three to four hours in the crowded jail cells. My father had to sign release papers and was given a court date as was everybody who had been jailed. The strike ended with the violence and the jailing of the union officials and the women and the children. I can still see the jail cell from the street to this day because it’s in the center of the court house and I can see the window to the cell where we were.”

Violence and tension within the community was reignited during the filming of Salt of the Earth. While relations between the film crew and the local community were friendly at first, anticommunists publicized the film which forced the filmmakers to respond to charges about their intentions for the film. Several townspeople felt it was their duty to denounce, and even forcibly prevent, communist sentiments from infiltrating their community. A politically fragile and racially charged situation further intensified once the local community feared the filmmakers had ulterior motives in making the film.

In the town of Central, New Mexico, the John R. Storz American Legion Post had developed an “Un-American Activities Committee”, and, during the filming of Salt, Leroy B. Bible, committee chairman, urged the Senator Dennis Chavez to help “clean out” (qtd. in Baker, 2007) the Communists. Soon after, the lead actress of Salt, Rosaura Revueltas, was arrested for having illegally entered the United States. During interrogation, federal immigration officers kept questioning whether she was a Communist, whether the motion picture was a Communist picture. Revuelta’s arrest not only stalled production of the film but also incited more tension among the filmmakers, strikers, and their local community.

Earl Lett, a local pharmacist and anticommunist, along with two dozen or so others, attacked the crew and strikers during filming. The next day, four vigilantes shot at Clinton Jencks’, union organizer, car. Later, a cavalcade of about 250 cars drove through Santa Rita, Hanover, Bayard, and Silver City in opposition of the film. “‘Citizens’ organized the parade, one participant stated, ‘to show people we don’t like communists or what they are doing'” (Baker 228). “By taking the law into their own hands and running ‘undesirables’ out of town” Baker asserts, “…Grant County anticommunists were simultaneously waging a local battle in the international Cold War and drawing on the history and mythology of vigilantism in the American West to justify their actions” (229).

Ultimately, all of the violence surrounding both the strike and film divided a community which is still fragile to this day. Baker reflects, “…it is worth examining the mechanisms by which Local 890 members both built and inhibited ‘community'” (141). The strike and Salt revealed some of the class and ethnic divisions that had existed for many years prior. Even if some people sympathized with the strikers, they did not take kindly to the perspectives of “outsiders” within their community. To some, these outsiders were a symbol of agitation who served only to “stir people up”. For others, however, people like Clinton Jencks and the filming of Salt were a symbol of necessary change. Nevertheless, throughout the decades following the strike and Salt, the historical and cultural wounds of the Grant County community and its relationship to the mining industry and to one another remain open.

courtesy of Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

courtesy of Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

courtesy of Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

courtesy of Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

courtesy of Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

published in On Strike and On Film (Baker, 2007)

published in On Strike and On Film (Baker, 2007)

published in On Strike and On Film (Baker, 2007)

References:

Baker, Ellen R. “Political Consciousness and Community.”On Strike and on Film: Mexican American Families and Blacklisted Filmmakers in Cold War America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ©2007., 2007.

Salt of the Earth Recovery Project: Digital Archive, https://saltoftheearthrecoveryproject.wordpress.com/.