Background:

Music is often a significant part of social resistance movements. Music unites people and provides these movements focus and resolve.

In Nigeria during the 1970s, Fela Kuti created Afro Beat music as a way to protest the oil company regime of Nigeria. His global hit song “Zombie” denounced Nigeria’s military dictators. In South Africa, the indigenous Mbatanga music helped bring about the end of apartheid and it spread a message of peace and reconciliation in that nation. In Chile, Victor Jara wrote songs about his country’s struggles, generating the Nueva Cancion (New Songs) movement aimed to unite South Americans against their military dictatorships. In Brazil, songwriters like Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, and Rita Lee created the Tropicalia movement as a form of protest against the Brazilian military junta. In Australia and New Zealand, indigenous songwriters composed songs that sparked a reclamation movement that is still active among artists today such as Alien Weaponry.

The U.S., in particular, has also had many musicians and songwriters who have, over the decades, brought about social resistance.

Music lifted spirits and united protestors during the Jim Crow Era while strengthening their resolve. One song emerged as an anthem for the movement, “We Shall Overcome.” Although the song’s exact origins are unclear, most scholars agree that it has roots in African American spirituals and in particular, a hymn titled “I’ll Overcome Some Day,” by Charles Tindley. Folks sung “We Shall Overcome” repeatedly on the marches from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama. It resonated with the protestors and became associated with the Civil Rights Movement cause. When Billie Holiday sang about “Strange Fruit” hanging from the trees, she was railing against the lynching and horror in the American South. Aretha Franklin brought her gospel music out into the streets with marching protestors as they demanded “Respect”. Curtiss Mayfield united the people with his song of hope, “People Get Ready”, and Stevie Wonder continued that tradition. Bob Dylan wrote one of the most popular anti-war songs of all time, “Blowing in The Wind”, and the Canadian Native American singer, Buffy St. Marie, offered a similar message with “Universal Soldier.”

Jazz musicians as well such as Charles Mingus and John Coltrane used song titles and instrumental melodies to incite social and political resistance. John Coltrane composed “Alabama” in honor of the four girls killed in the Birmingham church bombings. Even with just a song title and a melody, instrumental Jazz allowed the listener to create their own story in their mind.

Social resistance in the form of “story-songs” get people thinking, talking, and doing.

In Mexico and the American Southwest, these “story-songs”—called corridos—have become fundamental not only of social resistance movements but the culture itself. Songs of resistance and corridos have become a significant part of both the Empire Zinc Mine Strike and the Salt of the Earth film, cultural identity.

Jenny Wells Vincent, a classically trained musician turned folk-singer, performed songs rooted in social resistance at gatherings during the 1930s—1960s in New Mexico. In 1949, Vincent and her husband, Craig, opened the San Cristobal ranch as a vacation refuge and summer camp for political progressives. It was here where Clinton and Virginia Jencks, key figures in the strike, met Paul and Sylvia Jarrico, blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers. Several source texts suggest, had it not been for this chance meeting, Salt of the Earth would not have happened.

Among the many artifacts of Local 890 during the strike are mimeographed texts of the “Corrido del Empire Zinc,” sung at meetings and on the line to raise spirits. It features the memorable tune of the “Corrido de Cananea” about a miner on a parranda.

Enrique LaMadrid, Professor Emeritus at the University of New Mexico, along with his friend and fellow teacher, Nacho Quinones, worked to record and highlight several corridos based on labor and mine strikes. Their CD and the “Nuevo México, á ¿hasta cuándo?” CD are in special collection at the Center for SW Research in Zimmerman Library at the University of New Mexico. The latter one was part of the Smithsonian travelling exhibit entitled “Corridos sin Fronteras.”

The Salt of the Earth Recovery Project website explains:

“In [Enrique LaMadrid’s] fieldwork [he] was after a number of mining corridos to include examples of strike corridos, and mining disasters. [He] found the above ballads, plus the ‘Corrido del Morgan Jones’ about a disaster in the mines of Madrid, NM. [He] was looking for the ‘Corrido de Dawson,’ the deadliest mine accident in the history of NM. Years later, friends from Madrid gave [him] the text, which [he] passed on to Dolores Huerta, who grew up in Dawson and lost relatives in the explosion. Three years ago [he] heard that this corrido is still sung in the communities of the San Luis Valley.”

Nacho, who grew up in the Silver City region and now lives in Albuquerque, continues to perform corridos for the community. Some of these corridos include:

“El Corrido de Santa Rita” –a memorial to the town that was eaten by the big copper mine east of Silver.

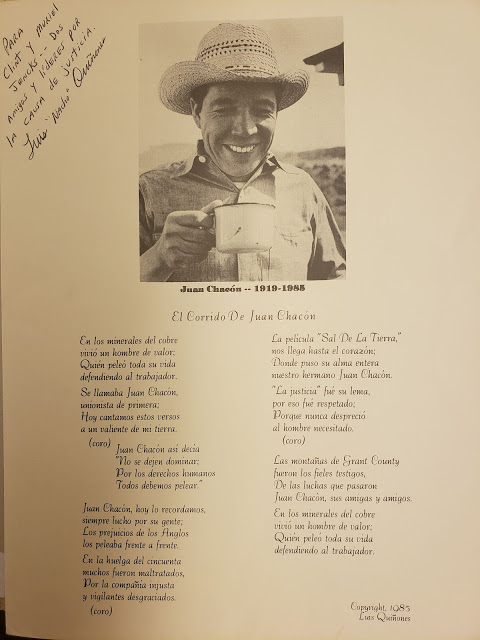

“El Corrido de Juan Chacón” – a tribute to the strike leader who played himself in the film. Nacho sang it at his funeral.

“El Corrido de Reies López Tijerina” – composed and sung for Reies at his 80th birthday, and revised later for his memorial service.

You can listen to Nacho’s “Corrido del Empire Zinc” here:

Exercise #1:

Do you know any songs about social or political resistance? If so, what are they? Click the links on some of the songs/artists mentioned previously, listen, and reflect on their message. Then, write a brief review on one of them.

What do you think is the song’s central message? Who do you think is the intended audience? What is the song’s purpose? In other words, why do you think the song was created—what were the circumstances that allowed the song to come alive? What in the song intrigues you most? What is confusing or unsettling? What would you like to know more about, either about the context of the song or the artist’s intention(s)?

Exercise #2:

Think about those who, today, experience social and working conditions like those of the miners, women, and families in the strike. Are there people in your life or community who experience similar conditions?

Watch this short video featuring Juan Dies, an educator for Sones de Mexico Ensemble, on writing corridos.

Consider writing your own corrido about a social issue that impacts you, your family, or others in your community. Like Enrique LaMadrid and Nacho Quiniones, you can also collaborate with someone in writing the corrido. Do you play an instrument? If so, consider playing or recording your corrido for an audience.

You can also submit your work for publication here.