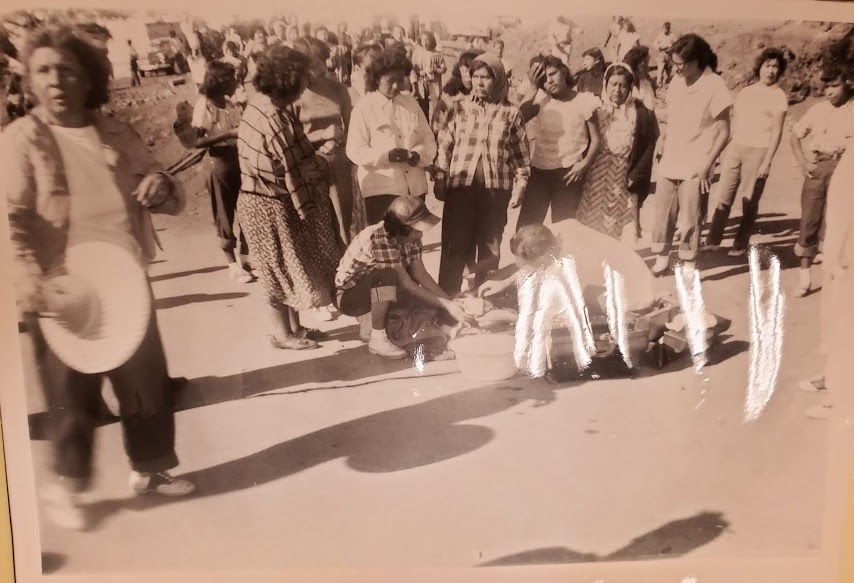

courtesy of Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

from The Poetic Table of the Elements. Clinton Jencks Collection. Special Collections, Archives, and Preservation (SCAP), University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder.

The strike, history of the Grant County mining region, and the film weave together culturally significant understandings of race, ethnicity, labor, and gender in the twentieth century.

Mine-Mill

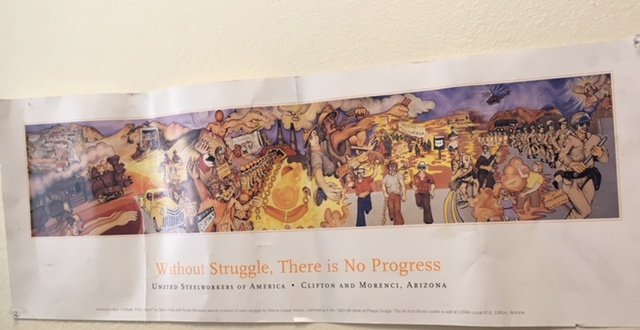

The Mine-Mill union provided a platform for the Mexican American working class to challenge ethnic and class inequality in the workplace, in their local community, and–with the help of the Independent Productions Company–in film and popular culture.

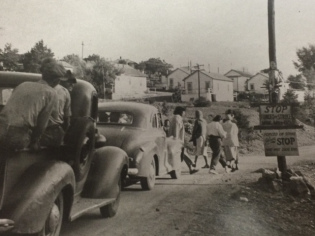

1930s: Mine-Mill, a well-documented left-wing union with ties to the Communist Party, enters Grant County. Mine-Mill’s commitment was interracial and interethnic labor organizing, in particular, among Mexican laborers in the Southwest and Midwest during the Depression.

1940s: Over the course of this time, workers and organizers with Mine-Mill significantly eradicated the dual-wage system in the southwestern mines. After World War II, members and leaders expanded their mission to address not only economic but political and social inequality. In 1949, Mine-Mill was expelled from the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) for failing to shed their communist influence.

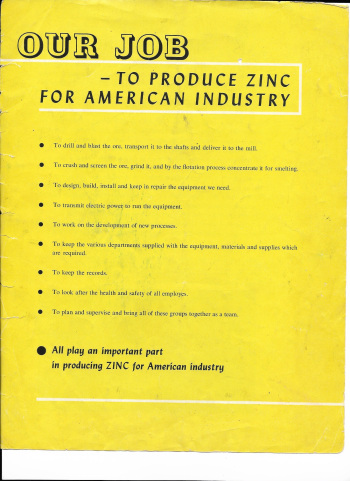

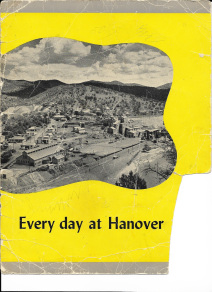

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

The Local 890

The history of the Local 890 intersects at both communist and anticommunist positions. Because of its ties to Mine-Mill, communism rested at the foundation of the Local 890’s structure and actions. However, this foundation was not openly acknowledged. Some 890 members and leaders did, in fact, belong to the Communist Party, specifically because it was a useful tool for addressing Mexican-American work claims. After World War II, however, mining managers reasserted their power over workers by using the threat of the domestic Cold War as a weapon against labor disputes. Ultimately, the the Cold War rhetoric divided the union. Several believed that a left-wing union could not possibly be democratic and represent the interests of its members. Nevertheless, because Mexican-American miners were historically part of a much broader Mexican-American labor and civil rights tradition during the 1930s, many of the 890 did not particularly care whether some of its members were communists. Their mission, first and foremost, was to “expose management’s anticommunism as a cynical pretext to push Mexican American workers ‘back in their place'” (Baker 9).

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

Gender Roles and Attitudes

Women in mining towns seldom found work, so they were dependent upon their husbands to provide economic stability. And yet, their unpaid work in the home and the community was crucial to the sustainability of the mining industry. While this dynamic ultimately would make for strong solidarity among men and women in the mining towns, general attitudes about gender and labor during 1950s often fractured solidarity.

In Mine-Mill Local 890, different models of masculinity both coexisted and conflicted with one another. The Local 890 men were able to establish ethnic solidarity on the basis of their shared experiences as miners and financial household providers. When the strike would eventually come underway, however, these models were called into question during the strike. Baker explains

“An aggressive masculinity, combined with the breadwinner ethic, proved important in creating class and ethnic solidarity during the [building of the union]…but when women’s picket duty in the [strike] called upon men and women to rethink their household relations, this same model of masculinity threatened the very class and ethnic solidarity it had helped build” (10).

As mentioned previously, Mine-Mill’s mission acknowledges the working class inside the broader community as opposed to the workplace. Mine-Mill also has historically been militant in its leadership. This dynamic simultaneously granted women a more significant role in the 890 and its activities as well as challenge the power and gender relations of the union itself.

Women’s Leadership

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

published in Salt of the Earth Recovery Project Digital Archive

Women’s leadership roles have, historically, come up against the tradition of patriarchal authority. For Mexican-American women in Local 890, this leadership grew from their own understanding and experiences as housewives in working-class mining camps as well as their eventual participation in union meetings and activities.

With the permanent injunction against the men during the strike, the women were able to bring attention to household issues and concerns related to the strike–the strike, in essence, was not only about equality for the miners but to acknowledge the work of women in the home and community. And although the broader prevailing gender attitudes limited their power, the experiences and protests of the Local 890 women revealed the “importance of feminism in Mexican American labor history, even where feminist organizations were absent” (Baker 11). When confronted with their husband’s and society’s resistance during the strike, the Local 890 women insisted on leadership changes both in the household and the community.

For a rural community in New Mexico, these demands were in stark contrast to the conservative family dynamic of 1950s America. It was the women’s roles in the strike that eventually excited blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers to tell their stories in the summer of 1951.

Reference:

Baker, Ellen R. On Strike and on Film: Mexican American Families and Blacklisted Filmmakers in Cold War America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ©2007., 2007.