San Cristobal

The story of Salt of the Earth begins late summer 1951 in San Cristobal, a small town near Taos, New Mexico.

Clinton and Virginia Jencks, who helped establish the Mine-Mill Local 890 Union in Hanover, New Mexico, and had a major role in the Empire Zinc Mine Strike, drove up the Rio Grande Valley to San Cristobal. The Jencks family needed rest from the demands and battles of the strike, so they drove westward to the San Cristobal Valley Ranch owned by their friends, Jenny and Craig Vincent.

Unlike a traditional ranch, Jenny and Craig’s mission was to foster community among political progressives seeking sanctuary from the tensions of the Cold War. It is here where the Jencks family met Paul and Sylvia Jarrico. The two couples got to talking, and Paul explained how he had just been blacklisted from his Hollywood screenwriting career. He described the blacklist allowed he and other blacklisted filmmakers the freedom to make films and tell stories on their own terms. Clinton Jencks, the weight and fight of the strike still looming, told Paul:

“We’ve got a story to tell, let me tell you. You know, we’re down on the Continental Divide in the southwestern corner of New Mexico and nobody knows were on the planet. And we’re engaged in what for us is a life and death struggle for ourselves and the existence of our union and nobody knows about it” (qtd. in Baker, 2007).

The Jencks’ went on to tell the story of the women’s picket, and Paul and Sylvia felt convinced they had found a story they wanted to tell, drove south to Hanover and picketed along with the women of the local 890. Soon after, the Jarricos returned to Los Angeles certain they had found a story that would make for “irresistible motion picture material” (qtd. in Baker, 2007).

The Jencks and Jarricos formed a friendship at the ranch that stemmed from their shared experiences of Cold War repression. The Hollywood blacklist stifled the Jarricos access to significant financial resources necessary for filmmaking, and the Jencks’ worked for a progressive union that had been expelled from the CIO in 1950. In short, each family had come under major scrutiny for “Communist domination” (qtd. in Baker, 2007).

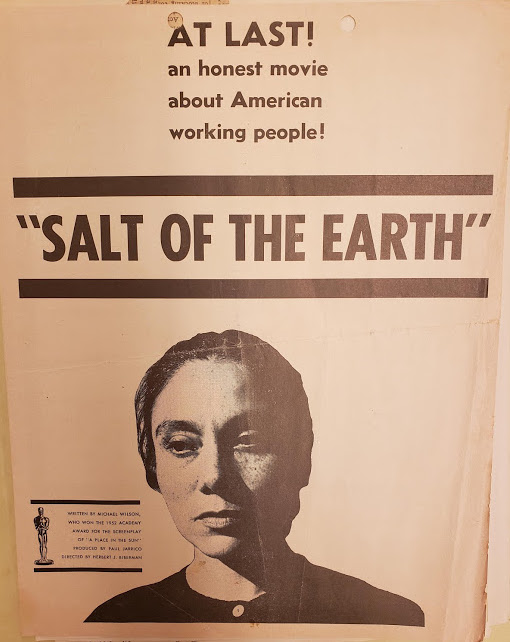

It was a complicated journey for the Jarricos, who, ultimately, along with other blacklisted filmmakers–which came to be known as the Hollywood Ten–were able to finance their own production company with the help of two groups of investors: those who supported their political ideologies and those who simply wanted to profit from the filmmakers talents. Their company, known as the Independent Productions Corporation, raised about $95,000, and by the summer of 1952, the Jarricos and the production company approached Mine-Mill international to collaborate on the filming of the women’s picket in Hanover, New Mexico.

Filmmaker-Striker Alliance

The filmmakers–Paul and Sylvia Jarrico, Sonya Dahl Biberman, Herbert Biberman, Michael and Zulema Wilson–made clear from the start that they wanted to capture the strike and the experiences of those involved as accurately and truthfully as possible. Gabriel Melendez, in Hidden Chicano Cinema, explains:

“Community approval was especially important since many mine families were operating from a deep conviction that the film project was a testament to their ‘burning desire for an end to racial discrimination’ in Southern New Mexico” (91).

So, the filmmakers set out to develop “sustained and close working collaborations with the people whose they wished to bring to the film” (Melendez 91). Screenwriter, Michael Wilson, took care to ensure these collaborations between Local 890 members and the professional film crew succeeded. Wilson interviewed several women on the picket line to better understand their role in the strike. He spent about a month in Grant County making sure not to “draw attention to himself” (Baker 193). He listened carefully as the women on the picket line explained the struggles of the strike–how the strike initially began as a struggle for ethnic equality, but once the women took over the line, it transformed into something much more significant. He concluded that “Only after men accepted women as equals, and Anglo and Mexican American workers allied with one another could the mining families sustain and ultimately win the strike” (Baker 193). After three months or so, Wilson felt he could write his screenplay.

Instead of focusing on the historical and political nature of the Local 890, Wilson’s script centered on personal relationships. Wilson contended that this angle would allow viewers to “…identify with the characters and appreciate the transformations they underwent. …to portray the kind of conflict–one between a husband and wife–that had been largely neglected by the union until the Empire Zinc strike brought it to center stage” (Baker 193). The Jarricos made clear early on that the Local 890 members would have final say on all decisions related to the script. For their part, the Local 890 members objected to particular scenes that would have led to cultural stereotypes.

One member, Lorenzo Torrez, objected to a scene in which Esperanza uses her dress to wipe a beer spill. He insisted it reinforced “the stereotype that Chicanos are dirty, and that they aren’t smart enough to use a towel” (qtd. in Baker 194). Another member felt that the screenplay was too focused on the “liberal white man–modeled after Clinton Jencks–saving the Mexican masses” (qtd. in Baker 194). In another instance, the men overruled an adultery subplot, and the women overruled one involving “too much drinking”(Baker 194). Several Local 890 members appreciated how Wilson accepted the criticisms and made sure not to let his own socialized beliefs influence the direction of the script.

Another aspect of this collaboration that shaped the cultural significance of Salt comes from their onscreen role as primary and secondary actors in the film itself. As Melendez points out “The selection of Local 890 president Juan Chacon the male lead certainly broke with film conventions of the day. Herbert Biberman…argued loudly for the use of amateur [actors] drawn from the community…” (96). Total, thirteen of nineteen official cast were nonprofessional, in other words, members of the Grant County Mexican American residents and union members. Several other actors from the Local 890 appeared as extras.

The careful way in which the filmmakers crafted Salt of the Earth creates “a new kind of popular culture, one in which working people themselves, allied with artists, would dramatize their own struggles” (Baker 196). Further, it reveals “a more fully rounded view of [marginalized] men and women creating their own history and acting on their own agency and determination” (Melendez 96).

References:

Baker, Ellen R. On Strike and on Film: Mexican American Families and Blacklisted Filmmakers in Cold War America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ©2007., 2007.

Meléndez, A. Gabriel. Hidden Chicano Cinema: Film Dramas in the Borderlands. Latinidad: Transnational Cultures in the United States. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, [2013], 2013.